One Breath Two Breaths: Jaiyoung Cho

Jaiyoung Cho has been working on abstracted objects that are deconstructed into polygonal units and, conversely, assembled from polygonal pieces. The process of deconstruction and reassembly is a trajectory that reverses the order in which we perceive things. The fixed individual objects are difficult to categorize as either concrete or abstract, and the objects are once again placed in a frame. Like skeleton and organ, the object and the frame mutate and unfold, one becoming an appendage of the other and feeding off the other as the frame supports the object or the object becomes part of the frame.

The assemblage of polygonal fragments is a coherently assembled form, yet it repeats and expands. The frames bind the objects, but also support their transformation and escape, maintaining a balance between restraint and overflow. The artist may have borrowed Deleuze's notion of the sculptural (de)structure of the 'Rhizome', a vine that tangles without a center, the principle of things being reconstructed on a differential basis, as the object and the frame mutate independently but complement each other and expand into a network.

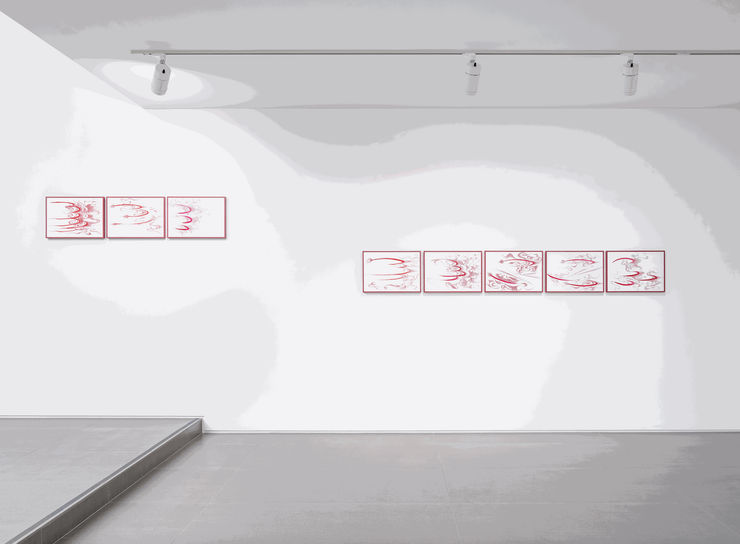

In her 2025 solo exhibition ⟪One Breath Two Breaths⟫, the artist attaches content to dry formality and crosses both ends by applying a sculptural grammar to the context of ethnographic culture. Deconstructed and reassembled, objects and frames coalesce into knots that either clump together to form a mass or unravel again. The knots and knotted objects remind us of tribal communities that are sensitive to the external environment, post-dualistic networks, the (non-)existence of the outside from the secularized human world, and excess and de-boundaries. In order to materialize this, the artist connects symbols and iconography that bind reality and draw boundaries even in a transcendentalist worldview. For example, she uses circles and horns as sculptural archetypes. If on one side there is a basic shape with a complete form, on the other side there is a sharp form that intervenes in the completeness, and the artist presents the bird's head as the junction of the two. The bird emerges as a mediating and eclectic material, connecting place to place, life to death. I wonder if the artist, who breaks down the sculpture into units and reconstructs it, places it in a state of independent fixation, but somehow leaves behind things that she cannot capture, imagines a motif of connection and the role of art to visualize it.

Whereas her previous works have used cardboard as a material, she has recently turned to thread and fabric. Relying on their elasticity and permeability, the artist weaves dots and lines together with stitches and knots instead of glue. Suspended like a mobile, the flightless bird multiplies its form without being fixed. This grammar of binding and unbinding is a kind of witnessing, a weaving of red mourning that reaffirms the inability to fully grasp what has emerged.

She varies and branches not only with materials but also with her interpretation of the frame. Rather than fixating on the frame as a confining device, she uses it to her advantage. The boundaries it creates function as an invitation to look outside, a signal for connection. From bondage and restraint, the centers of the sculpture, which connect fragmented things like puzzles and jigsaw puzzles and draw scattered molecules back together like air, take the form of wings and waves, and are then confined by the frame and pointed outward. Even if it stands only as a shell and a superficial pattern, the act of reading and interpreting everything as a shell creates wings from the shell, connects water and disperses air. The frame functions as a restraining device for liberation.

Nam Woong (Art Critic)